In the field with wildlife biologist Imogene Cancellare

Imogene Cancellare is not scared of lions, tigers or bears. She refers to them as, “Big, sexy carnivores,” and feels she has a healthy respect for the beasts. The 29-year-old wildlife biologist has worked with many species, from croaking frogs and crawling newts to meandering foxes and sneaky bobcats. She may, she admits, have a slight, reasonable fear of waterfowl. “They go for the eyes,” she noted.

The evolution of Imogene

Imogene spent the first 10 years of her life on a farm. She was always close to the circle of life and in contact with the Earth, she says. When her family butchered animals she wanted to watch, to see muscles, organs and tissues. She was already interested in natural history and the “nitty-gritty” of science.

“Most people who like animals at a young age want to be veterinarians,” Imogene shared. She, too followed that career path through undergrad until realizing her interests had changed.

During a trip to Australia in 2008, Imogene studied echidna and foxes at the University of Queensland. She learned about the conservation of native species, animal husbandry and wildlife management.

Upon returning to the states, she interned at Carolina Tiger Rescue between 2009 and 2010. “It’s not a place you go to pet tigers,” Imogene assured. “They focus on conservation issues.” There, she cared for exotic cats, binturongs and kinkajous. She helped make their meals, provide minor medical care and even designed enrichment activities.

During the fall of 2011, friends offered Imogene the opportunity to do research in South Luangwa National Park in Zambia. She jumped at the chance to see zebras, lions and other local species. The group camped right outside of the park, and fell asleep to the sound of singing hippos. But not before this misadventure…

I once got a little drunk and followed a hippo around a campsite. #ecologistconfessions

— Imogene Cancellare (@biologistimo) March 29, 2016

Far removed from her new ungulate friends, in the winter of 2011, Imogene studied bobcats near Glacier National Park on Flathead National Forest. She says the experience was ‘saturated in awesome.’ At the time, she was very interested in felis, or species of cats. She wanted to be a cat biologist but realized, “Those types of jobs don’t exist.”

She participated in various wildlife-related research trips and internships before earning a master’s degree in biology from West Texas A&M in August, 2015.

These days, Imogene gravitates toward mesocarnivores like bobcats. These animals eat 100 percent meat yet aren’t necessarily at the top of the food chain. She also does a lot of work with amphibians.

In her most recent position, Imogene has been working at the Savannah River Ecology Laboratory in South Carolina. There, she studies population genetics, which consists of researching individual relationships across species. She spends time in the lab sequencing genes and noting variations between allele frequencies and patterns.

Imogene also researches landscape genetics, or how a population changes due to its physical environment. A stream, for example, may be a barrier for one species, leading the populations on either side of the water to have different genetic variations.

Much of her fieldwork involves gathering data. She uses live traps, which allow her to capture animals without harming them. The creatures are then temporarily anesthetized while Imogene and her fellow researchers extract DNA, blood, teeth and hair samples as necessary.

Imogene has live-trapped many species, from gray foxes and bobcats to salamanders, newts, coyotes, gopher tortoises and more. She jokingly refers to raccoons as “trash pandas,” noting that while many animals cower inside the live traps, coons prefer to get grabby. Aside from scratches here and there, Imogene hasn’t had many negative encounters with animals. Although, she has been sprayed by several skunks, and swears by taking many baths and using vinegar to remove the intense odor.

The wildlife biologist also uses track plate boxes. These small, open-ended containers harbor a tasty morsel, like chicken, to lure an animal through it. The insides of the box are sticky, and catch bits of fur from passing subjects. The bottom is set to record the critters footprints as the animal wanders through. Unless, of course, it’s a bear.

Particularly-memorable creature encounters

On one field assignment, Imogene was in walking out to check track plate boxes. Upon arrival at the site where the devices should be, they were nowhere to be found.

“Bears go for that tiny piece of chicken and just whomp the boxes,” Imogene noted.

Her suspicion was right. A bear had retrieved the chicken, leaving the box crushed on a nearby cliff. Imogene had to crawl out to the very edge to grab the low-tech device and take it back for further analysis.

On another trek, Imogene and her partner gathered the data they needed and began heading back to their car. Upon turning around, they saw two sets of mountain lion tracks directly over their own footprints. The clawed-toes were facing the same direction their own feet had gone that morning. The mammoth prints were of a mother, and the smaller set from a kit. Imogene immediately regretted her decision to leave her container of bear spray back at the car.

“The safety pin was missing when I checked it before we started our hike. I knew my partner had his spray so I decided to leave mine,” she noted.

“When we saw those tracks we realized neither of us had brought our spray and we could be in trouble.”

As the duo walked over the footprints, an eerie stillness replaced the normal chatter of the woods.

“You can tell something is up when the birds and squirrels panic or go silent,” Imogene advised.

The biologist and her partner would shortly see that the mountain lion duo were only 10 feet away, trying to retreat. The cats were so camouflaged Imogene may have never seen them. Thankfully the humans passed with no incidence and made it back to the car safely.

“We both made stupid decisions,” Imogene shared. “Those were big kitty tracks.”

The biologist carries bear spray even if there are not usually bears in the area she is headed. The potent device could prove useful in the event she comes upon criminal activity, like a marijuana grow.

Science communications

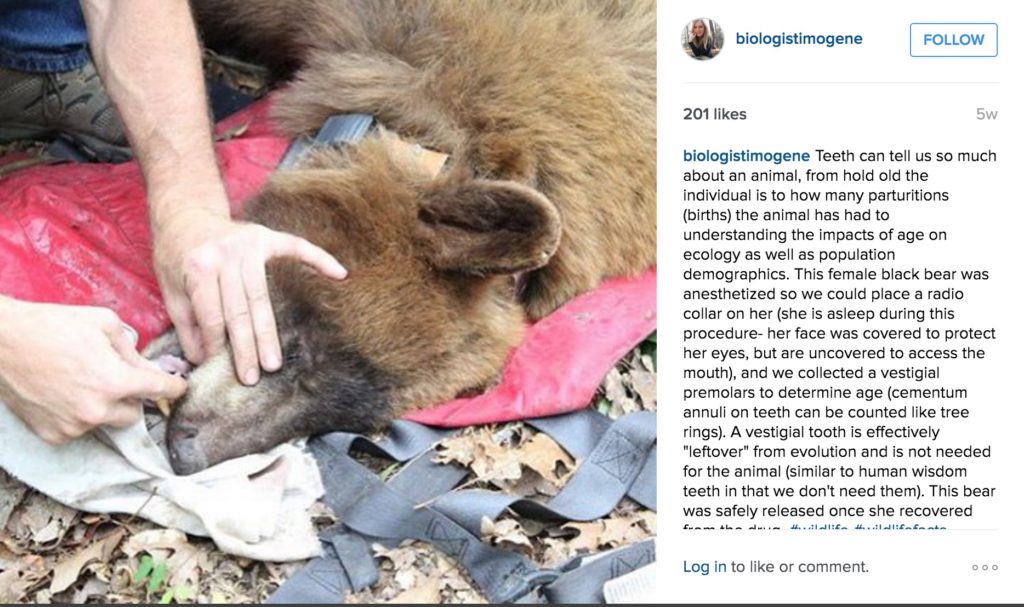

Browsing through her Instagram handle @biologistimogene, you’ll notice she uses the social media platform a little differently than most. Instead of simply sharing photos of herself scruffing the neck of an anesthetized creature she’s just trapped for research purposes, Imogene digs deep. Her captions are lengthy, but not so long you won’t read them.

She shares important information about whatever species is showcased in the post, like a marbled salamander or a red-bellied snake. Imogene includes information on where the animals live, what they eat and even why they look a certain way. Instead of shying away from words on the highly-visual medium, Imogene chooses to treat Instagram as a place for public education.

Her text is scientific, yet not littered with so much lingo that it’s academic. Imogene shies away that aspect of education, preferring to partake in more fieldwork while still providing information to the public. She hopes to get a PhD in science communications so she can continue using her knowledge and love of the wild to teach people the importance of wildlife conservation.

In one post, Imogene mentions collecting a bear tooth to saw into it, creating a cross-section. These carnivores teeth are like trees in that they feature rings that show how old they are. When a female bear has a baby, there is less growth because her energy goes to her cubs, so the rings are lighter and thinner. The biologist added that turtle shell scales, called scutes, are also lifestyle indicators.

Kids and science

“People are discouraged, girls in particular, from science areas because they are difficult and it’s not a lucrative field,” Imogene shook her head.

The biologist thinks the perception that girls shouldn’t get dirty also plays a part in the low number of women getting involved in science.

She urges parents of young kids to let them try new things and follow their interests. “Let them be curious!”

Imogene mentioned having recently seen a study that stated young kids in the UK spend less time outside than prisoners.

She was horrified that 74 percent of kids ages 5 -12 spent less than 60 minutes playing outside daily. The study notes this is partly due to youth’s easy access to entertaining technology, and also because of parental fears.

While it’s important to make sure kids are safe while playing outside, it’s also key that they get some daily woods/park/water time. Countless research has shown that fresh air and imaginative play, which doesn’t happen in front of the computer, are essential for brain growth and development.

While Imogene was lucky to be raised on a farm, she notes that this isn’t necessary to foster a fondness for nature. One great way to get kids involved in the outside world is through citizen science.

Citizen science

You may already partake in some aspect of this term without even knowing it. Composting, tracking the weather and even picking up a piece of trash on a walk are all examples of citizen science. Imogene shared a few vital ways urban-dwellers can add some scientific learning and even environmental consciousness to their daily lives:

- “Don’t ignore native species,” the biologist noted. She shared that many people think having an exciting outdoor experience must involve animals and environment that is NIMBY, or not in my backyard. Unfortunately, this leads to ignoring the animals that are naturally found in an area. Do you know what native species make your town or backyard their home? “You have to start small in order to build,” Imogene shared. Keep an eye on the birds, small creatures and bigger mammals that frequent a neighborhood pond or strut through your yard.

- Join a naturalist program. Kids might love getting involved in a youth-friendly science camp or class where they head into nature to identify species and discuss the environment. Adults, too, can benefit from these great programs. You can even earn a swanky certificate.

- Work on habitat restoration and rebuilding. Construction, modern waste and human progress have major effects on the environment. You have likely heard of the plight of various animals as they lose habitats due to human encroachment. Learn what species could use some help in your area by contacting a local wildlife group or college. Then, help to restore some of where the threatened species would normally live. This may mean planting trees and flowers, or even building nesting boxes for birds. You an unite the community through these positive initiatives.

- Plant only native species. “Learn what naturally grows in your area and don’t stray from that list when planting. These flora use less water and have a lower carbon footprint,” Imogene shared. Plus, that means fewer hours spent tending your garden!

- Don’t use pesticides or rat poisoning. They may cause unintentional harm to local inhabitants.

- Use cruelty-free ingredients in everything from cleaning products to makeup. This one’s a no-brainer.

- Swap vinegar for bleach. It’s better for the environment and less harsh on your home.

- Promote tolerance for the animals in your area. “These creatures live in your community, too. They don’t have anywhere to go,” Imogene explained. “Wildlife need food and shelter and water just like you.”

- Follow your interests. “If you think bees are cool, go talk to someone who keeps a few hives,” Imogene encourages. If you have kids, talk about what interests them about nature. Then, find a way to dig into the topic from academic and hands-on standpoints.

Get outside

Aside from citizen science, people can benefit from spending time outdoors as a way to get exercise and de-stress. Imogene recommends visiting state parks and hiking trails. If you want to join a group that partakes in outdoor activities, search Facebook, Meetup and the bulletin board at your local outdoor outfitters.

“You don’t need to have new or specialized gear. Grab an accountability buddy. Get past the hard parts and you’ll want to do it again,” She notes. Scheduling hikes, rides or paddles ahead of time and penciling them into your calendar may make you more likely to actually get out there. Adding a pal or two will make it all the more worthwhile.

“You don’t have to take big, sexy trips,” Imogene assures.

She added that one tool she always has on hand is a pair of binoculars. “Those little quarter things are for tourists and they don’t work.” Plus, who says a summit you’ve just bagged will have such a monstrosity? Pack binocs in your daypack instead.

When not doing work in the lab or the field, Imogene enjoys being outside. She loves hiking, particularly in Yosemite and Glacier National Parks, Flathead National Forest or California’s Sierra Nevada.

“The higher and harder the better,” Imogene said of her preference for tough hikes. “All you have is your legs and your endurance and your thoughts. It helps you figure out who you are and what’s important. My blood always feels cleaner after a hike.”

Imogene’s favorite places for seeing wildlife are not her beloved snowy zones. Instead, she says swamps and wetlands offer the greatest diversity.

“Just about everything needs water so there is better variation near it,” she noted. Snakes, turtles, toads, water birds and visiting mammals all spend some time at these important features. She can even identify frogs by their croaks.

The future

“You have to have a creative mindset to get science,” Imogene said. Not only is she a busy wildlife biologist, she’s also an artist. A beautiful painting of a great blue heron was the first thing we noticed about Imogene’s home. It turned out she was the creator!

The biologist also runs her own learn-to-paint company when she’s not doing fieldwork for herself or helping local students. She’s moving to Texas shortly to unite with her fiancé who is a grad student. At the moment she’s applying to jobs and planning to continue her education in the near future. She’s hoping to get a YouTube channel up soon that offers similar content to her Instagram, so keep your eyes peeled.

She’s also the very first Whoa ambassador! This means you might spot our Whoa logo on some of her gear, and we may share some photos back and forth. We love Imogene’s mission to promote science and environmental stewardship and are so stoked to have her as part of the Whoa team!

To get glimpses into Imogene’s awesome studies and fun personality, follow her here:

On the Web – www.biologistimogene.com

Instagram – @biologistimogene

Twitter – @biologistimo

I have followed Imogene’s posts, tweets, blogs, Instagram for years. She is one of the most delightful, accessible, and interesting wildlife biologist that I follow. I have learned so much from her about particular species and also about how to live in a sustainable, compatible way in this world. Glad to see her here and glad Whoa recognizes her uniqueness. Hang on to her; I really believe she has big things ahead!

Hi Heather!

We completely agree, Imogene is such a wonderful, smart woman! She’s one of those people you know is going places! Thank you so much for following her on social media and for checking our her Whoa Mag article! Happy trails! – Whoa