From Sydney to Mt. Vinson

At the end of 2019, I bid farewell to my parents, embarking on a month-long solo trip to Nepal. This trip was my imitable version of a schoolies celebration (following the end of my last year of schooling).

The first two weeks would be spent trekking to Everest Base Camp, while the next two, teaching English in a rural village. Little did I know that this trip would determine what I would do for the next four years of my life.

On the 29th December, we landed at the infamous Tenzing-Hillary airport in Lukla, stopping just shy of the brick wall at the end of the runway. It didn’t take long to see why this landing strip was dubbed one of the most dangerous in the world.

Tall Himalayan mountains on either side easily dwarf the runway, and because of its length (or lack of it!), it is angled upwards by about 10 degrees Celsius to slow planes down.

Stepping off the tiny plane, heart still racing from the dramatic descent, I was already in awe of where I was. The cold initially took me by surprise, but I relished in the environment, surrounded by my beloved mountains and seemingly a world away from my bustling city life back home. This was the starting point for the trek to Base Camp, which would involve nine days of uphill and four days of knee-jarring descent.

For the trek, I organized for a guide to accompany me, mainly for safety reasons. We set off at a cracking pace, and the dusty road winding through Lukla soon petered out to a narrow path.

The first day was a short one, passing through villages with an abundance of trees (they could survive at the lower altitude). We dodged yaks and their heavy loads and admired the simplicity of village life in the mountains.

We soon arrived at our first tea house (the basic accommodation we would stay in for the night), and I settled into my room, still trying to process the events of the past few days.

Before the trip, I felt a growing sense of anxiety and wondered how I would cope with the challenges. I had never experienced temperatures this cold or altitude this high and had never been away from family and friends for such a long time.

Nevertheless, I felt strangely at peace in this teahouse. I loved being in the middle of nowhere, where no one could contact me, and I could focus on just the basics – eating, sleeping, walking.

I also knew that this would be the lowest altitude on the trek, at 2600m and the air would only get thinner and colder from here. I tried not to dwell on my doubts and enjoy the present moment.

Over the next few days, we gradually ascended the Khumbu Valley, stopping every night in a teahouse along the trail. So far, I had found the trekking surprisingly easy. I felt the effects of the reduced oxygen, but I managed to cover the ground fairly quickly and not burn out going uphill.

After the day’s hike, I would stay in my room in the teahouse, writing in my diary, going through photos on my camera, and reading a book. The alone time was something I quickly learned to treasure.

With so much time inside my head, I guess I shouldn’t have been surprised when I caught myself planning my next adventure – long before this one was even over! I have always been a future-thinker and love setting goals to give me a purpose in life.

For the hike, one of the books I brought with me was a story of an Australian girl who became the youngest person to complete the ‘Polar Hat Trick.’ This feat involves skiing to both poles and crossing the Greenland ice cap. I’m one of those people who sees others do interesting things and wonders if I could do that too.

It must have been an afternoon nestled at around 4500m that I had the first inklings of conscious thoughts on having a polar trip as my next adventure. Reading through the book, I felt a growing sense of excitement welling up inside me.

In my room, it was around -15 degrees Celcius, the first time I had been in such temperatures, and I knew it was only going to get colder as we headed up. Still, I was feeling strangely positive about being in such a foreign and unforgiving environment.

I guess I made the unconvincing link that -15 and -50 degrees Celcius weren’t too big of a difference. The logical part of me said to wait it out a bit longer, and decide if a polar trip was something I really wanted to do after I finished this trek. As much as I tried to shake off the thought over the next few days, the excitement kept coming back.

I am a firm believer that if the excitement of an idea is still present after three days, I am meant to do something about it. As we trekked higher into thin air and freezing temperatures, I started formulating a plan.

I first visited Antarctica at the age of 14 onboard a cruise with my family. The coldest, driest, and windiest continent on Earth quickly captured my imagination, and I wondered what was hidden beyond what we had seen from the boat.

I left feeling amazed but also unsatisfied. I yearned to experience more of the harsh environment – to venture to areas that could only be reached by foot. In hindsight, it was an experience that would help shape a life-changing dream.

On the ninth day of the trek, we reached Everest Base Camp. I was immensely proud of what I had achieved with both body and mind and was surprised at how well I had coped in the challenging conditions. There was one last challenge to be conquered on the trek.

The morning after reaching Base Camp, I woke up early to climb Kala Patthar (5545m), the highest and coldest point on the trek. By then, my room had become worse than a freezer, settling in at around -25 degrees Celcius.

I couldn’t feel my toes. I did a half sit-up, shining my headtorch down towards the end of the bed, and noticed that the extra blanket thrown on top of the sleeping bag had failed to cover my feet. They had probably been cold the entire night.

Normally, I would be anxious about frostbite setting in but for some absurd reason (probably the lack of oxygen playing with my brain), I bounded out of the warmth and coziness of my sleeping bag and was absolutely delighted to have been thrown this challenge in preparation for my polar trip.

It cheered me way too much to know that this would be something I would have to get used to over the next few years. Soon, I may well wake up to temperatures as low as -30 every day on an expedition.

We left the teahouse just before the first rays of light and started the two-and-a-half-hour climb. As we neared the peak, it became increasingly difficult to breathe. One step would leave me bent over like I had sprinted 100m, and the air was so cold it almost felt boiling, scorching my throat as I gasped to get enough oxygen into my system, but eventually, we made it.

At 5545m, the peak was by no means impressive. It was minuscule compared to the surrounding Himalayan peaks that were mostly 3000m taller. Still, the experience gave me the confidence that I was physically and mentally capable of withstanding the cold and altitude.

Having completed the most trying parts of the trek, I finally allowed myself to delve into my polar dream. As I reflected on the trek so far, I realized that being in sub-zero temperatures was something I thoroughly enjoyed. As far as I was concerned, the colder, the better. It’s something I still can’t quite explain.

Polar Planning

I knew I wanted to return to the wild continent that had first caught my imagination four years ago. Antarctica would be my next destination and a dream I resolved to work on for the next four years of my life.

I decided I wanted to incorporate my love for mountains into the expedition and immediately settled on including a summit of Mt. Vinson (the tallest mountain in Antarctica). The initial idea was to ski from the sea of Antarctica to Vinson and continue to the South Pole, unsupported and unassisted.

I also knew that I didn’t want this trip to be purely for personal interests, so I decided to raise funds for a charity with my training trips and the final expedition. Since I was already a supporter and firm believer in the work of the Fred Hollows Foundation, I settled on having them as the charity of choice.

In the following weeks, as I stayed in the rural village and poured over maps of Antarctica on my phone (yes, there was a signal!). I quickly realised that it was going to be a hell of a long journey from the sea to Vinson, let alone skiing onto the pole, so I settled on just doing the sea to summit ascent.

Every day after teaching at the school, I went back home to pour over more accounts of people who had done similar expeditions. I got in touch with a world-renowned adventure company and asked if they would be on board to help facilitate my trip. They said yes. It felt amazing to have them help with this project, and it assured me that my dream could become a reality.

After further research, I couldn’t seem to find an account of anyone who had skied to the summit of Vinson from the sea before. Whilst it was encouraging to know that a potential first was on the line, I tried hard to make sure this wasn’t my main motivation.

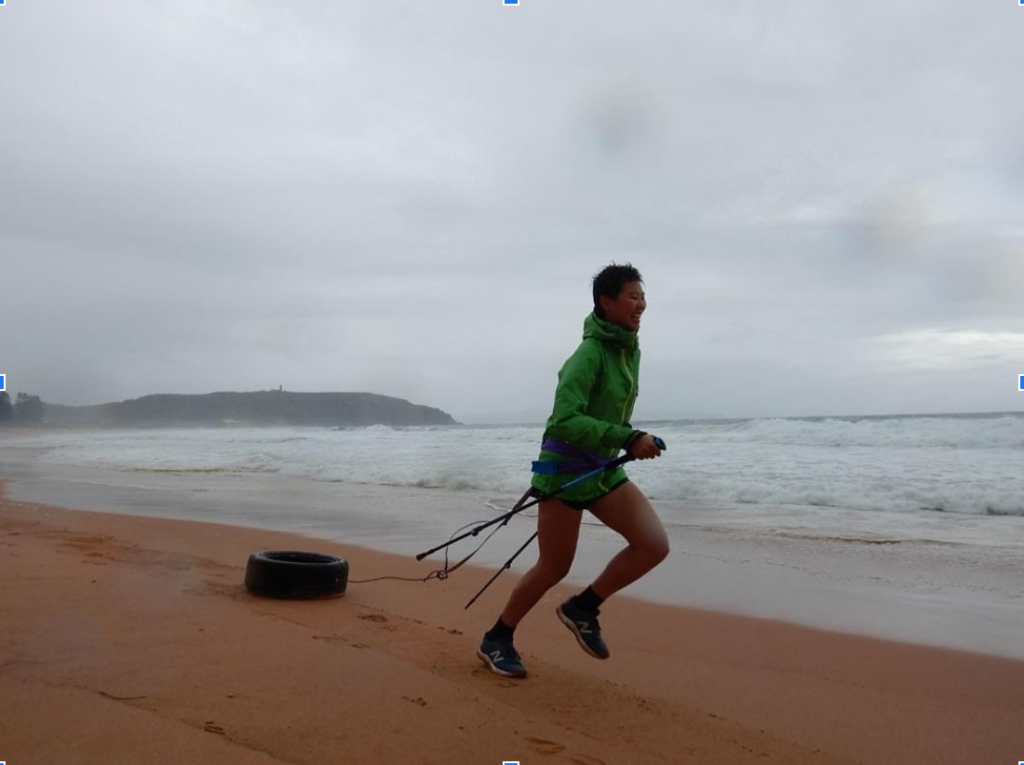

I wanted to climb the mountain from its true start at the sea, unsupported and unassisted, dragging my gear in a sled with no resupplies. I see this as the purest form of climbing, something which will make things much harder but much more rewarding.

I am writing this during the coronavirus pandemic. During this forced downtime, I have been able to focus on the planning and training aspect of this expedition. Over the next few years, I will be undertaking various training courses and expeditions in preparation to ski from the coast of Antarctica to the summit of Mt Vinson. I am beyond excited to see what the next few years will bring!

About the writer

I am an 18-year-old University student and outdoor adventurer based in Sydney, Australia. I love anything outdoors – hiking, trail running, swimming, climbing… My next adventure project involves skiing from the coast of Antarctica to the summit of Mt Vinson (the tallest mountain in Antarctica). If you would like to follow along on my journey, please visit my blog, on Facebook (Stephanie Ho), or Instagram.